Casestudy 08Bangladesh

Building inclusion through the

Planning Aid programme

- description

- further information

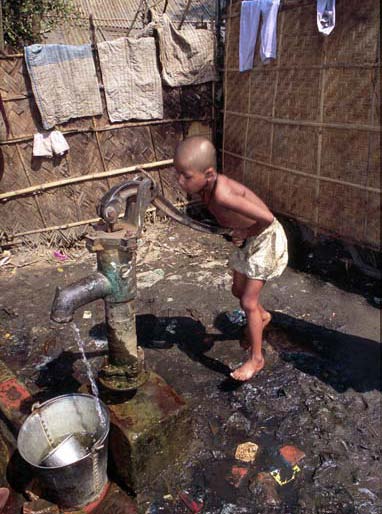

© Wateraid

A local NGO, Dushtha Shasthya Kendra has helped residents of some of Dhaka’s squatter settlements gain access to public water and sanitation services. In Dhaka, the agency responsible for water provision, the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DWASA), is mandated to provide connections only to households who can demonstrate legal tenure of their plot. This effectively excludes the large majority of slum dwellers. Persuading DWASA to install water points in squatter neighbourhoods was an important breakthrough that demanded many years and efforts of negotiation as well as important skills to gradually build the confidence among stakeholders that ways exist for informal communities to access formal utility services with a win-win outcome.

DSK had been working among the slum and squatter neighbourhoods of Dhaka for several years when it undertook to act as an intermediary between slum communities and the public water authority to enable the establishment of water connections in some of Dhaka slums. When slum communities expressed their willingness to pay for water supply services, DSK offered the municipal water authority the opportunity to serve as guarantor on their behalf for the security deposit and the regular payment of bills. DWASA officials eventually agreed to waive their usual policy and approved two water points in poor settlements of Dhaka, in 1992 and 1994.

Based on its experience with its first initiatives, DSK then worked at developing a replicable model for sustainable water supply for the urban poor. They managed to negotiate with DWASA the launching of a pilot project in 12 slum communities, provided that the cost for delivering the services would be recovered within the existing institutional framework. They successfully obtained permission from Dhaka City Corporation (DCC) to build water points and to cut roads on lands owned by DCC. The UNDP-World Bank Water and Sanitation Programme, the Swiss Agency for Development and Co-operation and the international NGO WaterAid provided technical support, as well as the initial funds in the form of kick-off loans.

The objectives were to build bridges between the water utility agency and potential user communities through advocacy and intermediation and encourage changes in the local institutional environment to facilitate the supply of water to the urban poor. In parallel, DSK helped community groups to mobilize and organize themselves in management committees for the water points and latrines. This included building their capacity to manage the water points and ensure prompt and regular payment of water bills, and meet supervision and maintenance costs, as well as repaying the capital cost. DSK also provided them with technical assistance to establish and maintain water connections as well as ancillary facilities. Dr Dibalok Singha of DSK explains ‘the challenge was to demonstrate and prove that such initiatives are successful; and on the strength of such experience to influence and push local governments to make real investments in such projects to the benefit of the depressed target groups’.

The water delivery model developed by DSK in Dhaka has proven to city authorities that when they are willing to pay, informal communities can be capable and responsible managers of essential services, as well as reliable clients for the relevant service providers. For DWASA, this represents an effective system for regularization of illegal connections and corresponding increased revenue. Moreover, equity of supply to the urban poor can be viewed as politically rewarding for those local government officials who have been supporting the programme. Since the inception of the project in 1996, DWASA has become increasingly confident in extending its service facilities to slums and squatter settlements. 88 water points have been established in 70 slum areas, benefiting more than 200,000 people, whilst about 12 water points have been paid for and handed over to user groups. The project’s success in showing the potential for informal communities to be reliable clients has prompted the water authority to allow communities to apply for water connections on their own behalf without the need for a guarantor. The water authority is also cooperating in the replication of the project in 110 community-managed water systems, benefiting around 60,000 slum dwellers, with plans to expand the arrangement to one of the largest slums in the city with over 250,000 inhabitants.

Gradually, DSK hopes to transfer responsibilities to communities themselves, including approaching and negotiating with DWASA and DCC. Introducing the communities to these agencies may help establish their right to water and sanitation services. Indeed, the initial years of careful but persistent negotiation through the setting of successful precedents have induced a change of mindset in the Dhaka authorities and utilities. It has also brought about significant changes in power relationships between slum dwellers, landlords, the water utility and city authorities. Dr Singha acknowledges that working with official bodies such as DWASA or DCC takes time ‘but slowly and surely acceptance is reached’. Clearly, this depends on the commitment of senior managers in these key agencies, but it is also essential that field-level officials be willing to cooperate in the initiative. Influence from outside agencies and international organizations is also a major factor to help convince sceptics within local authorities and utilities.

The model has started a new wave of thinking and, in close association with WaterAid, has been replicated to scale with other NGOs and municipal authorities throughout the country. Lessons from the model have also encouraged the draft final Dhaka Water Supply Policy to include community participation as a policy priority, mentioning that communities will provide suggestions for better services and help raise awareness of stakeholders on the water policy, as well as monitor the implementation of government policy and plans. The policy furthermore commits to ensuring full water supply coverage to the urban poor of Dhaka’s slums. More than a successful negotiation experience, the DSK model also proved an effective entry point for urban utility reform in favour of the urban poor.

The model has started a new wave of thinking and, in close association with WaterAid, has been replicated to scale with other NGOs and municipal authorities throughout the country. Lessons from the model have also encouraged the draft final Dhaka Water Supply Policy to include community participation as a policy priority, mentioning that communities will provide suggestions for better services and help raise awareness of stakeholders on the water policy, as well as monitor the implementation of government policy and plans. The policy furthermore commits to ensuring full water supply coverage to the urban poor of Dhaka’s slums. More than a successful negotiation experience, the DSK model also proved an effective entry point for urban utility reform in favour of the urban poor.

© Wateraid

Go back to case studies listing

Akash, M. M. and Singha, D. (2003) Provision of Water Points in Low Income Communities in Dhaka, Bangladesh, paper prepared for the Civil Society Consultation of the 2003 Commonwealth Finance Ministers Meeting, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam, 22–24 July, Commonwealth Foundation, London.

Matin, N. (1999) ‘Social intermediation: Towards gaining access to water for squatter communities in Dhaka’, Water for All Series (May), Asian Development Bank.

Rokeya, A. (2003) DSK: A Model for Securing Access to Water for the Urban Poor, WaterAid Fieldwork Report, WaterAid, London.

Singha, D. (2001) Social Intermediation for the Urban Poor in Bangladesh: Facilitating Dialogue between Stakeholders and Change of Practice to Ensure Legal Access to Basic Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Education Services for Slum Communities, paper presented at the DFID Regional Livelihoods Workshop: Reaching the Poor in Asia, 8–10 May, DFID, London.Ziaul Kabir (WaterAid Bangladesh)

4/8 Igbal Road

Block-A,

Mohammadpur

Dhaka-1207

Bangladesh

Tel / Fax: 9128520 / 8115764

Dr. Dibalok Singha

Executive Director

e-mail: dsk@citechco.net / dskhq@citechco.net

Bangladesh House

97/B, Road 25,

Block-A, Banani,

Dhaka – 1213,

Bangladesh

Tel: 880 2 8815757, 8818521

Fax: 880 2 8818521

Ziaul Kabir

Programme Officer - Advocacy

e-mail: ziaul@wateraidbd.org

2nd floor, 47–49 Durham Street

London, SE11 5JD

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 20 7793 4500

Fax: +44 20 7793 4545

e-mail: wateraid@wateraid.org

Website: www.wateraid.org